All images © Naoko Matsubara. Ashmolean Museum

I thought I knew hands by studying them at medical school. Dissected, to start with: skin and fascia revealing muscle and bone. Next, photographed: a lit-up metropolis of busy cells and crisscrossing arteries, veins and nerves. Then, finally, alive and whole in various manifestations – swollen, arthritic, pale, jaundiced, eczematous, clenched, wringing, animated – telling a story I somehow needed to make sense of.

But there are many ways of discovering the "cleverness" of human hands, as distinguished woodcut artist Naoko Matsubara points out in her introduction to her new book, In Praise of Hands. Her own epiphany arrived after the birth of her son, whose hands, she observed, were so freshly formed yet so able to "pull, push, twist, scratch, hit, pat, squeeze, squash, hold, pinch, shake, point, poke, search, clap, rub and so forth" that it inspired her to create the series of woodcuts on which this book is based.

In Praise of Hands consists of 31 of Matsubara's woodcut prints, spanning from 1974 to 2020. The last one had been specifically designed to complement a work by prize-winning poet Penny Boxall. For each of Matsubara’s earlier prints, it was Boxall who had been engaged to create an accompanying poem. The result of the collaboration is a rich, deep synergy.

In a woodcut print – or, at least, my simple understanding of it – an image is carved into the flat surface of a block of wood. This surface is then covered with ink, which is printed, and the carved bit remains free of ink. So, what you finally see is as much about what has been removed as what remains – about absence as much as presence – and in a way this chimes with Boxall's analysis of Matsubara's method: materiality combined with suggested character through absence.

Boxall writes that In Praise of Hands is “primarily a series of portraits” where the characters are depicted through the details of their hands. I would agree. Firstly, most of the woodcuts are of disembodied hands. On closer inspection, these hands are performing a range of activities, in different imagined environments, telling the stories of their invisible owners using a “precise vocabulary” of colour and form.

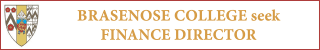

Apparently, Matsubara cuts directly into the wood without sketching the image on it first. Maybe this explains the bold, flowy, spontaneous impression I got, as opposed to mapped-out precision, even in more detailed works like Ah Spring!, which shows a pair of hands, fingers interlocked, engaged in the task of holding a branch laden with blossom.

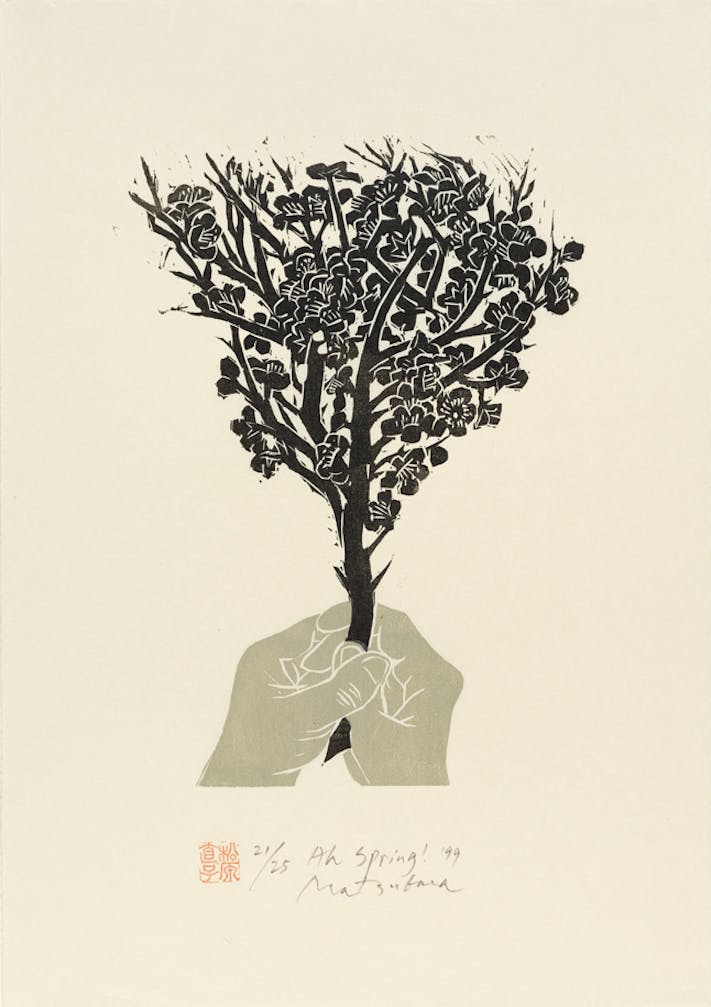

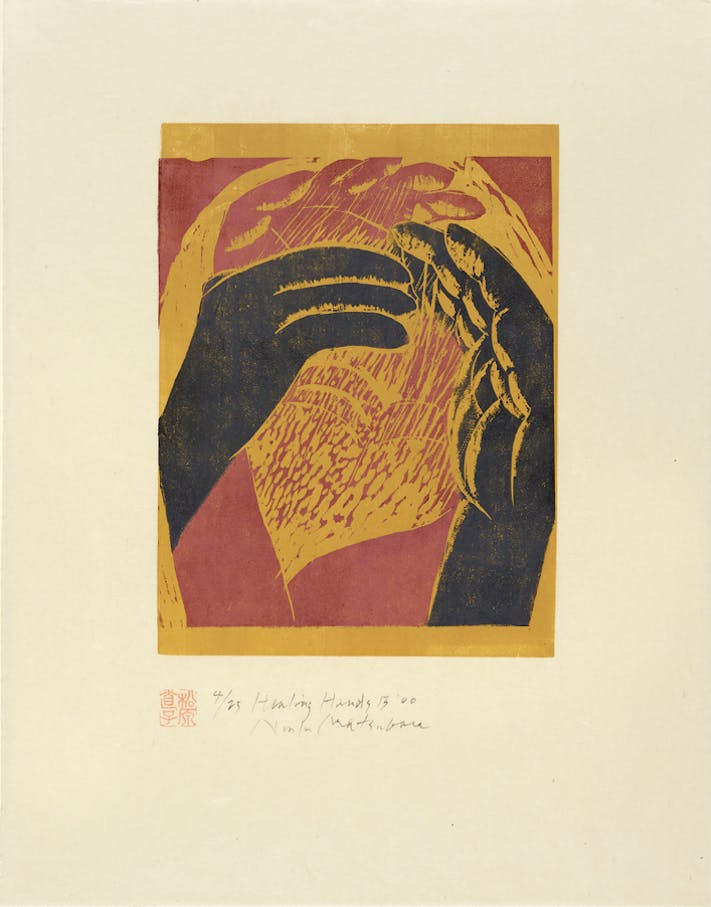

I feel this is a deceptively simple book. Each time I looked at the pairings of art and poetry, I noticed something different. I was also struck by the versatility of both artists and the resulting diversity of pieces, even within such a small collection. Healing Hands B (2000) was one of my favourites, because of its maturity, both visual and verbal, in capturing the reciprocity within an interaction between healer and healed. The pandemic has put a new perspective on the role of hands - in particular, our need for human touch - and the 1994 work, Buddha's Hand, takes on a new significance as it shows us "how to reach for acceptance: between forefinger and thumb, lightly."

It would have been remiss for this book not to feel comfortable in a reader’s own hands, and I'm happy to say that its proportions and the quality and texture of the paper were lovely. I wished that the prints had been a bit bigger, so that I could have seen the detail more clearly. Additionally, whilst both artists wrote individual introductions, I would have liked to have understood more about the collaborative process itself. These minor points aside, there is a satisfying sense of completion to learn that the designer of the book is no other than its chief instigator: Matsubara's son.

I was initially drawn to this title because of my personal and professional attachment to its subject matter; it would have been the book I wanted to write myself, but from a totally different perspective. Now, I find myself thinking that in these woodcut-poems, as in medicine, human hands tell so much, and in doing so instil in the observer a feeling of wonder and awe. And in that sense, art and science are not so dissimilar after all.