A guide to growing your own in the city of Oxford. Lots of us do!

Contents:

Getting An Allotment

How to go about getting one

Most years, by the time the weather's got nice enough for you to be filled with a desire to roll your sleeves up and get outdoors, it'll be too late to get an allotment. But it is still definitely worth putting your name down on the waiting list, because the months will pass quicker than you think, you'll have even more plans for the allotment by then, and because you'll be filled with this desire next Spring too. While you wait, and indeed if you do want to do some growing but don't want a whole allotment to yourself, you would be welcome at one of the community / volunteer gardens. See our list here.

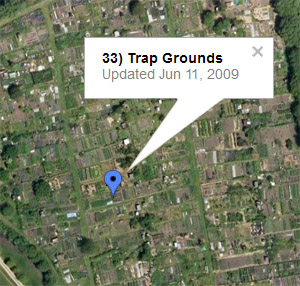

Click on the map snippet to see the Council's

full Google Map of allotments in Oxford

For all things gardening it helps to take a reasonably long-term view, not least because some fruit and veg won't even crop till the second or third year it's in the ground. This can be daunting, but it's probably also part of the reason you want to start allotmenteering. Assuming you decide to dive in and begin the whole process now, you'll need to ring up or email the secretary of your chosen allotment. You can usually find contact details either by going to the allotment and looking at the noticeboard, or by looking up the details on the web. The page listing all allotments in Oxford is one of the council's better webpages, being clear, informative and easy to find!

We found it all quite easy from there on. We picked an allotment ground which was a compromise in convenience of location vs length of waiting list. And we now have a lovely, full size plot, between three (and one non-digging member!). You can expect to pay around £20 for this in groundrent. This size of plot is supposed to be able to feed a family of four.

Sites in Oxford

There are 36 allotment sites in Oxford, varying considerably in size. Not all have a waiting list, but most in Oxford do. There will also usually be people already growing things in a site who would like more space, so outsiders on the waiting list have to compete with proven gardeners who can manage a plot and who haven't give up at the first sight of a slug. This is a little unfair in some ways, but in my experience it doesn't mean you won't get one, it just means you might be made to jump through a hoop or two. (Like turning up at the communal sheds for a couple of Sunday mornings at the right hour looking keen, or emailing back promptly and going to look at the plot in the rain!) Try to understand why this is being done to you, and not resent it. Keeping an allotment, as already mentioned, is not a short-term, NOW culture type activity. And the allotment committee want communally-minded, helpful, friendly sorts on board, who can weather a bit of discomfort.

The allotment year runs October - October, and often starts with the AGM. Anyone who's giving up a plot because they're moving, or for a planned reason, will probably do so then to avoid paying the new year's fees. So if you're on the waiting list at this point you might even get a cultivated plot in good order! In theory. By April or so the people who are naughty and haven't paid their subs yet might be getting prodded by the secretary, and so more plots may come up then. In some smaller allotment grounds there are stricter rules, and someone might get thrown off at any time of year for having their plot in very bad order. (Don't panic - this doesn't mean a stray weed, it means serious neglect!)

Some allotments with long waiting lists split up the plots, and give out a quarter or half plot to new members. Again, don't be churlish! Grow what you can, and if your bit is in good order they'll give you more when it's available. Now you'll be on the other side of the fence, desperately hoping they ignore the hopeful waiting list and reward your time and patience!

What is the point?

If it's so hard to get one, why bother? Well, there are many advantages to owning an allotment: exercise, thrift, growing without chemicals, social equality, working a bit of good English soil, introducing children to the miracles of nature and so on. But they do read a bit like government propaganda. I think in the end, the point is eating lovely, tasty vegetables, and the people who persevere with their allotments are the ones who've done it mainly for the food.

After all, having brighter, shinier, higher ideals is all very well, but as a payment for many hours' labour it just doesn't compare with a good soup.

The first year

The nicest advice I read last summer was that the first year you shouldn't expect to get much more than a third of a full-size plot into cultivation. We took on a thoroughly overgrown plot towards the end of April last year, and quite a lot of what we had planted suffered in the exceptionally warm weekend in May when we were away. This was pretty disheartening, compared with our fabulous plans, and that made it harder to keep going and keep up. (What saved us, if you're in this boat now, was the little feathery carrot tops coming up, and actually looking like carrots!)

We did many things non-ideally. The tomato plants went in late, and were so matted together their roots got damaged getting the plants apart. We had a lovely crop of green tomatoes just before the autumn frosts, and ate many of them fried. The aubergine flowered (purple) but didn't fruit. The spinach bolted without us eating a single leaf. And then we found the advice which said that is normal for a first year. I wouldn't have believed it before starting out, but I do now.

This year, of course, it will all be different!

Will I become nothing but a zealous allotmenteer?

Just because the image of allotments is old men in flat caps with hoes and young hippie types growing everything organically, that doesn't mean you have to become anyone else to grow stuff. The plants don't care who you are, or how much you've adopted an allotment creed. My fellow plotholders and I are still relatively sane, normal, well-balanced people, just ones with tasty potatoes.

Principles For Choosing What To Grow

Shallots & Charlottes

This school of thought says you shouldn't bother growing veg which are cheap to buy, like potatoes or onions. If you want similar you should grow shallots and specialist potatoes like Fir Apple Pinks or Charlotte salad potatoes. This is basically a financial school of thought - what gives you best yield in terms of the money you would save. There's probably an equation for it.

Grow what you want to eat

This approach is so sane it's a wonder nobody follows it. Essentially it stipulates that you should grow food you like eating and if what you want to eat (or indeed grow!) is just chillis, cauliflower and sweet peas (or just onions and potatoes) then that is your inalienable right.

However, this very weekend, I succumbed and bought a rhubarb crown, despite disliking rhubarb. Why? Well, rhubarb is a very allotmenty thing to grow and fits with my picture of what an allotment should be. So now I must give over a 1m radius to a fruit I'm not that fond of. Ah me. Of course, the rub is that perhaps when I've grown it myself I'll love the taste, and at least it'll vary my diet.

Fresh and Green

The things it is most worth growing are the foods that make most difference if they're fresh. So grow lettuce, herbs, salad veg and eat them instantly while they're all crisp and juicy. For this to work you obviously need to live very close to your allotment, or maybe just grow these in containers or window boxes at home.

Speciality veg

A slight extension to this is growing what you can't otherwise get, or can't otherwise get organically grown. So with the abundance of farmers markets in this area you might find it hard to spot a lack, but there's sure to be one somewhere!

I don't choose to grow asparagus, for instance, because we can get it so freshly from Binsey Farm in season. It takes up so much space on an allotment for the vast proportion of the year when it's not going to give you any return, that I'd rather someone else provided the floorspace for it, and I just got the results! But globe artichokes I really like, and not so many places sell them.

Heritage varieties

Afghan Purple carrots, Tutankhamun peas, Colossal leeks, Peasgood Nonsuch apples... if you grow heritage varieties you can at least be assured of some good names. Whether they taste better or whether they've been rightly forgotten by the world, you have to grow them before you know. And that's the point really, that these are varieties you'll never find in Tesco's, who only differentiate their pears by colour not even by name.

Growing heritage (or RHS award of merit) or any other distinctive breeds is one step closer to that feeling you get in a french market where there are 15 varieties of garlic available, all named, and no discerning gourmet would dream of anything less.

A French Market in Edinburgh. Photo: www.theedinburghblog.co.uk

Things that grow easily

Peas are not only delicious to people but sadly to pigeons as well. If you grow them you must protect the young plants with great care. So instead you might grow runner beans, which are not nearly so attractive to the feathered monsters when young. Or for some reason mange tout are reputed to be easier to grow and hardier.

Mind you, shortly after we'd just had the first delicious carrots (my god they were carrotty!) last September I read somewhere that carrots are notoriously hard to grow. Fortunately no-one had told our crop that.

English Veg

No, I'm not advocating the BNP take over the NSALG. I'm just suggesting that things which have grown well in the English climate for centuries (like carrots) may be easier to grow than pineapples, lemons and olive trees. But then that would be no fun, would it, without the challenge...

Little of everything

Avoid gluts by having only a couple of each type of veg you can think of. A good way to start out on a new plot, as you can work out what likes your soil type.

Fruit, flowers and Fowl

And perhaps bees, but they're not alliterative. These are considered optional extras by the hardcore (and I don't think resident hens are allowed on any Oxford allotments anyway though we did hear about a family who bring their hens to visit). You are allowed to grow flowers on your allotment if you so wish. And many people consider fruit a luxury rather than a staple, except for rhubarb which is apparently a veg.

If you want to grow apple trees on your plot you'll need them on Very Dwarfing rootstock (called M27). This means the tree can only reach a height of 2m because it thinks it's a crabapple. Otherwise, planting trees is usually also banned.

Perennials vs Annuals

If you want to make life easy for yourself you can fill at least some of your beds with perennials - plants which regrow next year all on their own. These include strawberries, fruit bushes / trees, asparagus, many herbs, perennial broccoli and some more obscure things too.

With perennials you don't have to worry in the same way about crop rotation, or digging the bed over completely from year to year. Just add plenty of mulch or compost in winter to boost your plant for the coming year. Hooray for laziness!

The downside is that you can't rotate the crops, that eventually most plants will need to be replenished (strawbs 3 years, rasps 12 years, asparagus 12ish), and that if you do get diseases and things it's more of a serious loss to the garden. You have to choose varieties more carefully too, if you're going to be stuck with plants for longer, and many perennials only start to be productive in year 2 (though you can buy 2-year old plants). You might have to read up on specialist care eg. pruning techniques to keep the plant useful.

Direct sown veg vs high maintenance seedlings

Onions, carrots, potatoes can all be sown straight in the ground where they are to crop. They survive the temperatures even in March. Many other vegetables need to be sown in seed trays, repotted, grown on, hardened off and eventually planted out. You can buy little plants if the faff does not appeal.

Cropping all year

If you only happen to like tomatoes and chillis then all your christmases will come at once, usually in August. To keep eating home-grown produce all year you have to do a lot of preserving. It's worth thinking a little about when things will be harvestable. Some brassicas can keep going all winter, if they're hardy. So while you might prefer spinach to cabbage, come January some fresh homegrown kale might be very welcome.

Incidentally, this is a fascinating thing - at the time spring is springing, seeds are being planted and the outdoors becomes appealing once again, that's the time there's nothing to eat. It's called the Hungry Gap, and it's why hares resorted to eating rye that was mouldy with ergot which produces a chemical much like LSD. Hey presto - mad March hares. This is something that 100 years ago everyone would have been acutely aware of. Now we have supermarkets, freezers and air freight and we've all forgotten.

Companion planting, Underplanting and Interplanting

Three Sisters grown by net_efekt on flickr, who we

gather is just round the corner in Wheatley.

Instead of neat rows 1' apart you can grow things in a more bushy fashion, with plants grown together. There's more info from growfruitandveg.co.uk.

- Companion planting often sees pairings like garlic and carrots, with the idea that garlic helps deter carrot fly. Poached Egg Flowers are grown near fruit, so that the insects are attracted and help pollination (and to eat pesty insects).

- Underplanting means tall plants can have a shade-loving crop grown around their feet, eg. sweetcorn with a carpet of courgettes. The traditional Native American Indian grouping is Three Sisters: sweetcorn, with beans growing up them, and squash roaming the shade underneath. More info here.

- Interplanting might mean parsnip rows (which have to be well-spaced) interspersed with a quick grower like radishes, which will be done and eaten before they all get big enough to bother each other.

With care you can achieve a real jungle, but if you overcrowd your beds you may need to add more nutrients at the end of the year and you may get wonky parsnips.

How To Tackle A New Plot

I think you have two basic choices here: chemicals, or no chemicals. We decided no thanks, not in a spirit of trailblazing moral fervour, but just on the basis we wouldn't use any until we had to, and we haven't had to. I don't really want to eat things which have had slug pellets all over them, but then we've been fortunate in how little slug damage we've had. Personally I'd rather have the endorsement of my cabbages in the form of a few bites out, than line the pockets of Glaxo and co. We occasionally get round to sprinkling coffee grounds and holly leaves around the cabbages, but mostly we hope the robins will just get hungry.

Of course on an allotment site there's probably every chemical under the sun on some patch of it somewhere, and it's worth remembering you'll never be able to control what everyone else wants to do. As long as everyone is careful with their aim, what each plot does shouldn't bother anyone else too much.

Non-chemical chemicals

include leafmould, compost (homegrown) and well-rotted manure. Wilgrow supply fabulously mature manure. It's horsebedding that's been rotted down so long you won't get weed seeds sprouting which can be a problem if your manure is still young and virile. They're local chaps, don't have a website, but their phone numbers are 08000 430124 or anytime 07990 970461.

Raised beds & strawbales

are helpful if you want your plants' roots to be warmer and drier than the surrounding soil. They're also good if you want things to grow deep. All you need is scrap planks and some stakes. Hammer the stakes in either side of the plank to hold it in place. Most people's raised beds only raise up a few inches, so the stake can be 8 or so inches long and hold in place very firmly. The weight of soil will be against the inside, so stake more firmly against the outside.

For very waterlogged beds you could try growing veg in a strawbale. Apparently courgettes like this, mediterranean sunhogs that they are. You cut a bit out of the bale, put in some compost/earth and plant in that. This should give your plant room to trail off the sides, keeping its feet dry. The straw rots down around the soil, and by the end of the year you can compost what remains of the bale. This is a trendy new idea and consequently you get billions of results if you do a google search!

Straw bales can be bought from Home Farm in Bladon, just on the edge of Woodstock, 01993 811463. They're £2.25/bale and you can choose Barley or Wheat straw.

Abandoned plot syndrome

Weedkilling. You might find, taking over an abandoned plot, that weedkilling is a good option. There seem to be weedkillers available which aren't deadly for years afterwards. We didn't go this route, so I don't know a lot about it.

We chose to dig instead, which is on-going hard work, but has suited us.

The other, non-chemical option is to rotavate, which is like a mini-plough. Many allotment sites will jointly own a rotavator. There might be a small charge, but there should be someone to show you how to use it. Beware, however, since it'll chop the roots into little bits. For some weeds (like nettles) that's the end of them, for others (normally the worse weeds like couch grass, bindweed etc) you've just sold arms to the enemy: there'll now be a new weed plant for every little bit of that rootstock.

In theory you should be able to tell from your weeds what your soil type is like. Ours was clearly fertile, as we could tell just by the height of them! You can be more scientific if you wish. But the good thing about a weedy plot is that it's lain fallow for a while, and that allows the soil to replenish the nutrients it might have lost in its last period of intensive growing.

Sadly there are no shortcuts: perennial weeds and pests can only be eradicated through hard work. Cartoon by Miranda Rose.

Preparation

Digging

If you want to know about digging, read Alec Bristow. He's a master on the subject, and I couldn't possibly recreate all his advice, which covers different ways to organise your digging as well as how physically to dig without straining yourself. Essentially digging should fluff up the soil so plants can poke their roots through it more easily.

If you don't dig carefully where you'll be planting your carrots they'll grow funny, because wherever they get to a hard bit of earth they twist. Take out weed roots now, to save on weeding later. A spit is the depth of the spade's head into the ground, and you can just dig one spit deep, which is fine. Or you can dig two spits deep, by digging out the topsoil, getting it out of the way, and loosening the next layer. It will have different nutrients in, so you shouldn't swap the top and second layers over. But it does give your plants more room for their roots, better drainage, access to more nutrients and so on. It's more ambitious, so perhaps it's one for purists and prizewinners.

If you're a real pro, you can go deeper. I heard a lovely story about a weatherbeaten old chap who had the most immaculate plot, with glossy veg springing up everywhere. He was asked his secret, and in reply he just stuck his walking stick in his soil and leant on it. It sank up to its handle.

If you dig in November and December you can supposedly just leave the clods whole, and the freeze-thaw process will break them into a fine, friable tilth without any labour on your part. This winter it was so solid and snowed over for the whole of December we don't know if this works in practice! Planting potatoes is reputed to be an excellent way to make your soil all lovely and fluffy.

Planning the layout

If you're going to plant fruit bushes, asparagus or anything which will be in the ground for a while site them reasonably carefully - maybe out of the way, maybe somewhere it'll be easy to get all round them to pick the berries. If you're wanting to plant really tall things like sweetcorn, beans up poles, or globe artichokes (which grow on a thistle-like plant about 7ft high) then site them where they won't shade the rest of your plot. And that's about it really.

Your annual crops should rotate position to lessen the problem of diseases which attack one particular crop, like potato blight. A 3-year rotation is standard. For layout the website www.growveg.com really helps. A subscription is not pocket-wateringly expensive and you can generate next year's layout from this, whereupon it warns you if you're about to plant the same veg in the same spot as last year.

Kit, sheds, budget generally

Your costs can stretch to hundreds and hundreds of pounds if you're not careful, as there is no limit to the amount of gardening equipment for sale. You're going to really need some things, and want others. But for quite a lot of things you'll have to pay in either time or money, and it's up to you which is in shorter supply.

Vital: tools - a spade, a fork, gloves, wheelbarrow, watering can (with rose to create fine spray).

Desirable: hoes, including a mattock hoe, little fork & trowel, shed, string, polytunnel, netting / chicken wire, canes, balls for joining canes, greenhouse, cold frame, flower pots, propagator, buckets, sickle, strimmer, twine and stakes, shovel, compost bins, fruit cage and so on...

Some of these are seriously only luxury options!

Buy a good spade and fork, and thick enough gloves to tackle brambles. Your tools should be balanced just above the head, where the metal of the handle stops and the wood of the handle takes over. If the balance is wrong it'll be a pain to use, every time. Don't get the biggest tools possible - they'll be too heavy and make life difficult. Don't buy really cheap tools. We bought a £5 spade, and upon jumping onto it to sink it into the earth, it bent.

A mattock hoe is very useful to break up earth. You swing it over your shoulder and its pointed head goes into the soil. All the work is done by the momentum of the tool, and it's surprisingly easy to use even for a girl (like me). But I wouldn't if there were children about!

Many people are extremely frugal on allotments, leading to some ingeniously re-used items. For instance a rusty swing-seat frame for growing beans all over, plastic bottle cloches and cane end protectors (to protect the eyes of the gardener, not the cane at all), and pallets for tiles/bricks which have sides to heap up your compost. But to find all these items if you don't have them knocking around might not be worth the time.

We have built our own shed, but the time it took when we could have been digging, and the cost of materials and beer for voluntary workers means it might have been easier to buy one. They start at around £100-150 but you may need base materials on top of that. Or maybe instead go for a walk-in plastic greenhouse (£60) and a lock-up box for tools.

You can spend lots and lots of money on seeds, or 79p per packet (35p from Aldi!) as you wish. There are noisy advocates of both approaches.

The Allotment Year

Calendar:

This calendar is on the Trap Ground allotments website, and it looks terrifically useful.

Remember IT'S A GUIDE! If you find you haven't yet planted up your seed potatoes and it's already May, don't waste time agonising about it, just do it when you can. Better late than never.

SPRING

March - May is known as The Sprint! It's the time everything in the ground is really waking up, so you have to get the post-freeze digging done as fast as you can, and get the plants in! Then you can just sit back, in the sun, and the only effort you'll have to extend from May onwards is eating the odd perfectly ripened berry...

Planting seeds

Most seeds can be either sown indoors and planted out or directly sown in the ground. Others, like carrots, must be planted directly in the ground because they'll find it impossible to recover if they have to be transplanted. But they're in the minority. Seeds germinated indoors then planted out can get going before the weather is warm, and are hardier by the time they have to withstand weather and pigeons.

When sowing, remember that one onion or carrot seed produces one onion or carrot. One tomato seed produces 50 tomatoes. It's easy to forget this when all the seeds are much the same size!

You can buy nice fancy propagators with clear plastic lids. Or you can use egg boxes, sections of looroll, newspaper cylinders, coir matting pots, big flowerpots with plastic bags on top to keep the moisture in, or anything else which comes to hand.

Every seed packet will tell you further instructions, like the depth in the soil the seed likes to be, whether it has to go a particular way up and so on. Different plants have their preferences, but remember they'd be passing through birds and growing any how if they didn't have us to help; you'll just give them a better chance if you follow the instructions.

Most people germinate more seeds than they need and pick the best plants to plant out. If none of your seeds from a particular packet germinate then return them and get your money back. This isn't just thrift - it may be useful feedback for the seed company.

Avocado stones need to be soaked, then sit up to their necks in water while they germinate. Potatoes too have specialist needs, and require chitting.

All seeds from all plants fall into two categories: dicotyledon or monocotyledon. Dicots come up as seedlings with two leaves, monocots with one. Monocots are rarer - lots of grasses are monocot, but the plants you'd most likely grown on the allotment from this category are onion family, and sweetcorn. These poke out first as a sort of rolled up spike, and each new leaf unrolls from out of the middle of the last one. This is easiest to think of as how a leek grows, because leeks get fat enough to see each leaf easily. Everything else is dicot.

This is only really important because it means you can't tell what any plant is from its first pair of leaves. You won't know if it's a worthy or a weed until it has its first distinctive leaves. Even frilly old tomatoes start of with a pair of rounded dicots like everything else. Dicots look like a child's drawing of leaves and are all pretty much the same shape, differing only in size. (This is because they're technically part of the embryo not the grown plant, hence the difference in shapes!) This year we planted many seeds in modular seed trays. When the greenhouse blew over all the earth was muddled up, and we scooped it into seed trays and set it warming up again. The resultant mishmash has been interesting to try and identify!

What is chitting anyway?

Chitting means starting off potatoes, usually by putting them in egg boxes in a coolish spare bedroom or similar, in the light, and causing the eyes of the potato to start to sprout. This gets them ready to grow, so they don't rot so easily even if the ground gets a bit wet after planting, and should cause them to crop earlier.

Where to buy seeds and plants

Don't plant supermarket garlic, potatoes, or apple pips. In the first cases you are probably planting strains less resistant to disease than you might like, and you don't want to introduce potato blight into your ground if you don't have to. In the case of apples there is a different and much more interesting problem, namely that apple trees are often grafted: with one tree's roots attached to another tree's boughs. This is good because it controls the height of the tree and so on, while growing nice fruit. However the pips will probably revert, and give you more of the rootstock tree, usually wild, sour and crab-appleish, not more of the top half tree with the tasty fruit. So for apple trees you really have to buy an apple tree.

There are numerous garden centres roundabout. Millets Farm is fun, because you can go an see the guinea pigs too. Yarnton Garden Centre is fun, because you can go and look at the fish and antiques too. The covered market florists sell seed potatoes, rhubarb crowns and a veritable array of seeds. Sylvesters on Magdalen Rd sells both seeds and plants (veg and flowers). And many other small shops might have a tray or two of homegrown tomato plants at that time of year.

Talking of which... outside the communal shed at your allotment you might easily find cheap tomato plants as someone will have carefully grown 30,000 seeds in a propagator and planted up the best 10 plants, leaving the spares for you. You'll also find spare plants for sale on Daily Info's Gardening page. Recently we've had herbs, tomatoes and strawberries going cheap.

Online we've used www.gardenorganic.org.uk for heritage seeds. They were prompt and helpful. And we've also ordered seeds from DT Brown: www.dtbrownseeds.co.uk. They're a very long-standing mail-order only company, with a no-frills, good quality, cheap and quick approach.

And according to Bob Flowerdew you can buy overripe things at the supermarket to grow, including pineapples.

Starting things off

Some plants shouldn't get too cold too early, and might want to sit in a greenhouse, poly tunnel or cold frame to harden off before they go in the ground. This also depends how the weather is, of course. Some plants need protection from horrible pigeons when small - our cabbages got jumped on very thoroughly last year. We made a sort of ridge tent out of chicken wire, until they got big enough to fight back.Peas get pecked to death, and this year some blasted pest bit the tops off all the shallot shoots! Gourmet bunnies, perhaps.

If you don't want to bother with all the cosseting you can buy plug plants, where someone else has done that bit! But do sow some seeds. There's nothing like seeing a green row appear from the earth.

Weeding, thinning, watering, other occult practices

Weeding is fairly obvious: once you know what your plant looks like, remove everything else. Little label markers are useful here, so you don't pull up something you meant to cherish.

Thinning means making your crop come out more evenly spaced and giving each plant more room. You might need to do this with a row of carrots, for instance, where you sprinkle the seed directly into the ground. You carefully sow too much so you are not left with gaps, but then you want to give the plants room to grow (or your carrots will come out wonky as they grow round each other). When you thin carrots you have to be careful to pull the baby carrot out cleanly without bruising the leaves of the plants you're leaving, and then dispose of the thinnings far away. Otherwise carrot fly smell the lovely fragrant carrot oil you've released into the air and whizz over to eat holes in them all. We found the best way of disposing of carrot thinnings was to eat them. You can pretend to be a giant raiding a dolls-house kitchen garden if it helps.

Watering. Some plants are thirstier than others, and I think you're supposed to keep fruit watered well when it is swelling and ripening, which is why 2007 year of disastrous floods was so good for apples. Plants will wilt if they're short of water, and if you give them a good drink then most things recover. Except for spinach, which bolts. In the bright sunshine you should pour the water on the base of the stem or on the earth rather than on the leaves, so the droplets don't act as tiny magnifying glasses and burn the leaves. If possible water in early morning and evening not at the hottest part of the day.

Bolting means a plant thinks it's in distress and immediately makes flowers and seeds in order to carry on the species in better times, rather than growing leaves and taking its time. Lettuces do this if they get too dry, cf spinach, beetroot, coriander and some others. Varieties will be grown which are described as Bolt Hardy (or Slow Bolt).

Hoeing, if done right, is a way of weeding standing up, and can also improve the moisture retention of the earth. See Alec Bristow's book to have the mysteries explained.

SUMMER & AUTUMN

It was a great big lie that you can just sit back in the sun now. In fact the reason the allotment holders twinning group with Grenoble never took off was because there was never a time in the year when the two parties were prepared to leave their allotments long enough to travel to see each other.

More Weeding

It never stops. As long as it's good conditions for growing your lovely little vegetables it's the right conditions for weeds too. See Alec Bristow's book for weeding with a hoe, standing up, with little effort.

Harvesting & eating things

Should be an easy one! See recommendations further on of good cookery books for what to do with your precious crops. In fact the only real problems are how you know it's ready to pick, and gluts. Re the former, try one and see how it is, is usually my approach. If it could do with ripening up then leave it a bit longer. If that's not possible (eg green tomatoes, frost tonight) then you can sometimes ripen things indoors on a sunny windowsill or locked in a drawer with a ripe banana. Or you enjoy it unripe - fried green tomatoes, salsa verde! Last summer we mostly ate things when they looked good, and that seemed to work perfectly well. Some plants like potatoes and onions are ripe when the top growth falls over and starts dying off. I'd recommend better books by better gardeners for info of this sort.

It is a terrible clich that growing your own veg means a month of courgettes, a month of tomatoes and so on. It's entirely true, though with judicious planting (sow some of the seeds one week, some a fortnight later, and not growing too many courgette bushes) you can minimise the problem. You also need friends without allotments, who think free courgettes are a luxury. Or you need to eat them all as baby courgettes. With such fresh veg you should just be able to steam it lightly and eat with butter and black pepper. Nigel Slater is good on recipes which are simple enough to enhance rather than smother the flavour of good veg.

Storing things

Some veg stores kindly (garlic can be dried and all the ends plaited together in an artisanally french way, potatoes can be stored for a while in a dark bag). Some can stay in the ground like cabbages and brussels sprouts. If you have to pick it you can do a number of things instead of eating it fresh: freeze it, turn it into jam, pickle it, store it in brine, or alcohol or oil.

Health Warning: Preserving in oil can be very dangerous with fresh veg: you can grow botulism, which is a serious food poisoning nerve toxin. Alcohol or vinegar will not allow botulism to grow, so really things should only go in oil if they're already dried, which defeats the object.

Going on holiday

You have three options: skiing, friends & neighbours or marrows. So either you go away when it's not prime planting or harvesting time, or you get other people to water & pick everything, or all your veg grows huge and neglected and some plants wilt a little. Actually it's not this bad, but if you do plan a month off in August I'd advise making some arrangements with a friend, preferably one who's on an allotment waiting list, terribly keen and very greenfingered.

Where To Get More (Better) Advice

Other allotment holders are always a good source of help and advice. Cartoon by Miranda Rose.

Books

There is no shortage of books about allotments. You can get ultra-glossy books filled with photos or mud-proof pocket-sized editions. You can get the old salt's guide to digging in potash, or the newby's funky activities on allotments for families with small kids. You can get books arranged by month, by veg, by soil-type, by pest or by recipe. I would recommend starting in the library, to give you a good idea of what sort of advice you want, and then buying things when your eyes are less starry!

Here are some of those which have come to our attention:

Growing advice

- John Harrison, granddaddy of allotment advice books. Essential Allotment Guide / Vegetable Growing Month By Month. Also has a website. I find him a bit dry and dull, but there's no denying he has a lot of experience. If you want to know how you ought to do something then he'll tell you, but since I know full well I'm not going to use the sort of galvanised nails for my braced fruit cage that he dictates then I get resentful. It's probably not his fault.

- Half-Hour Allotment - Lia Leendertz (RHS). Lovely pictures, sane approach, very choosy about her veg (advocate of the no potatoes or onions since they're cheap to buy approach). So what she does say is good but she's not the ultimate reference guid.

- How to Run an Allotment - Alec Bristow (Beautiful Books Ltd, 1940). This is a really straightforward book about how to do things properly. Written during the war, so there was no room in it for poncing about; it had to tell first-time gardeners clearly what was what as a matter of life and death. So a bit sobering, but really good advice.

- Gardeners' World: 101 Ideas for Veg from Small Spaces. Lovely, inspiring book (by which I mean it has good photos) of burgeoning planting ideas. Probably these are a bit too small and intense for the allotment, but they're well-planned and talk about which season to do things in, rather than which month.

Cookery advice

- Tender - Nigel Slater. Half cookbook half gardening journal, this is a nice reminder of why you might bother growing veg. Slater's recipes are, as ever, clean and pared down to the point where they do not always sound appetising. But they're excellent for bringing out the soul of each veg rather than just masking its taste with spices which is what I often end up doing if I'm not careful. This is food as jewel rather than fuel.

- Vegetable Book - Jane Grigson All the classic recipes, and the book is organised alphabetically by veg.

- a good Indian Cookbook, such as The Cinnamon Club Recipe Book, or 50 Great Curries of India - Camellia Panjabi (because Jane Grigson sticks mainly to European style cookery)

- other specialist cookbooks for allotmenteers (or for seasoned farmers market shoppers!) including the wonderfully-named What Will I Do With All Those Courgettes by Elaine Borish.

But beware - because this is a growth market there will be bandwagon-hoppers, who just throw together books without putting in any effort at all. I recently spotted The Great Allotment Cookbook: Over 200 Delicious Recipes from Plot to Plate. It has no author, which suggests no-one's love and care has gone into this that they're prepared to put their name to. Not a good sign!

Websites

- for planning: www.growveg.com which has free trial, or inexpensive subscription. Good features include clear pictures, a calendar showing when to plant and harvest your veglist, you specify the size of the plot, and for next year's plan you copy this year's and it remembers what has been where to make sure you rotate the crops. Also very funky and useful is free site www.allotmentor.com which allows you to: plan your vegetable plot, drawing beds and planting crops, with helpful hints on good rotation, plus generate your personalised vegetable calendar based on your plan, and keep notes on when you plant, cultivate, harvest, etc. so you can learn from previous years' successes.

- for buying seeds/plants: www.gardenorganic.org.uk and www.dtbrownseeds.co.uk are the two we've tried, and we'd recommend both.

- www.nsalg.org.uk is the National Society of Allotment and Leisure Gardeners. They have comprehensive info about plants and gardening, and also represent allotment-holders politically.

- www.allotment.org.uk is John Harrison's comprehensive website. The blog of the book, as it were.

- www.rhs.org.uk Royal Horticultural Soc is the Doyenne of gardening organisations. They're the ones who organise Chelsea and stuff. At RHS Wisley (just off the M25 near Godalming) there are sample allotments where the RHS test different varieties of veg to see what gives best pest-resistance, value for money for space and so on. The website has an A-Z search available even to non-members, so you can look up fruit, veg, diseases, pests, processes (like pruning) or gardening terms.

- The ever-friendly www.gardenersworld.com has a whole series of manifestations: website, blog, twitter feed, magazine and of course the BBC tv programme. If you're a beginner this is an accessible and not too patronising source. It covers not just edible crops, but all the gardening sphere - flowers, wildlife, ponds, decking, containers, hanging baskets, the lot.

- Ben Wilkins at studentvegetablediaries.co.uk provides step-by-step, real-time guides on how to grow veg at Uni. Simple but effective methods for sowing and growing in small spaces.

Other Sources - Media

- Film: Grow Your Own. Here is Daily Info's review, by Glenn Watson.

- It's a good excuse to watch The Good Life back catalogue, but only when it's too dark or wet to be outside, of course.

- Radio: Gardener's Question Time, Sunday afternoon, Radio 4 or anytime on the listen again and podcast schedules.

Meticulousness

Much as I love looking at those regimented allotments with beautiful matching raised beds, hospital corners, mown grass paths and not a weed out of place, I know that I am not really that person. I certainly haven't been for the last 32 years, and while it might be possible by supreme dint of will, I'm unlikely to start now.

Fortunately nature isn't much like that either. I haven't measured soil acidity to see if it needs lime, instead I'll just try growing some cauliflowers and see if they like it as it is. In short, it's heartening to look over an allotment and see that there are as many approaches to growing things as there are plots.This is because, ultimately, it's not you who does the growing. It's the plants. They'll have their favourite temperature, light intensity, moisture, acidity, companion plants etc etc. But they'll give it a go wherever. It's possibly to get very bogged down in the theory and never plant anything, when really the worst that can happen is a smaller yield.

So if in doubt I'd switch off Gardener's Question Time, and throw some seeds into the earth. You never know what they might do down there.