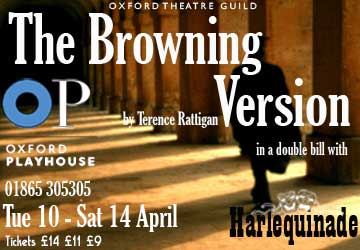

April 10, 2007

As a double bill, these two Terrence Rattigan plays make for odd bedfellows, sharing little common ground and demonstrating two distinct extremes of the author’s range. The Browning Version, unquestionably the stronger of the two, is a controlled and deeply moving study of one man’s realisation that everything of value in his life is fundamentally rotten. Andrew Crocker-Harris, a public school Classics master, had begun his career as an outstanding scholar but, owing to a harsh and objective approach to his pupils, has come to be nicknamed the “Himmler of the Lower Fifth”, largely for a self-acknowledged humourless approach to scholarly rigour. Having been forced into early retirement from the school, and having to take a menial position for the sake of his health, Crocker-Harris is further humiliated when the school refuses to grant him a pension. His wife, who is having an affair with his close friend and colleague, Frank Hunter, mocks his weakness and belittles him at every opportunity, and his pupils send him up mercilessly behind his back. The one moment of touching redemption, when one of those pupils presents Crocker-Harris with a leaving gift, is itself brought into question as the motives behind the gesture are speculated upon.

The role of Crocker-Harris was immortalised by Michael Redgrave in the 1951 film version of the play, leaving anyone familiar with that benchmark with high expectations. Nick Quartley tackles the role with a suitable gravitas and a clear awareness of Redgrave’s interpretation, portraying the character’s shattered faith in common decency with a convincing balance of pathos and stubbornness. Clare Denton, as his wife, openly enjoys the malice inherent in the part, and works well with Oliver Baird’s Hunter in completing the emotionally volatile triangle.

The play stands as a prescient vision of a postwar Britain in which the primary criterion for success moves from ability to popularity; the recognition, as early as 1948, that Crocker-Harris and his ilk were becoming obsolete, is the key to its importance in theatre history. Beyond this, though, the play is also a beautifully handled examination of the tension between private despair and public dignity. It is interesting, to anyone familiar with the rather melodramatic climax of the film, to experience afresh Rattigan’s original, sparse ending which leaves the outcome of Crocker-Harris’s final act of defiance entirely unresolved. It is a brave move, and all the better for it.

In contrast, Harlequinade is a light-hearted and fast-paced farce satirising the world of the touring theatre company in the mid twentieth century. A tale of vanity and spinelessness, the play is set on the stage as a production of Romeo and Juliet, as two ageing stars rehearse the roles they have been playing for decades, and for which they are clearly no longer suitable.

Here, Rattigan seems uncertain as to the nature of the genre he is working in; what begins as a witty and verbally dextrous dismantling of Shakespeare’s doomed romantics soon descends into an increasingly implausible pantomime of mistaken identity, Brian Rix-esque misunderstandings and a very tenuous storyline involving bigamy, illegitimate children and amnesia, whose resolution seems beyond the author’s reach. That said, there is plenty of sharp dialogue along the way to entertain, and strong performances, particularly from Simon Vail as the fading Romeo, make the time pass amiably enough.

This unlikely paring, the serious work with the broad farce, is made all the more curious by the author’s deliberate decision to mount them as companion pieces. It is undoubtedly the former that has stood the test of time, but as an evening’s entertainment, these two short works represent good value from an impressive amateur company.

The role of Crocker-Harris was immortalised by Michael Redgrave in the 1951 film version of the play, leaving anyone familiar with that benchmark with high expectations. Nick Quartley tackles the role with a suitable gravitas and a clear awareness of Redgrave’s interpretation, portraying the character’s shattered faith in common decency with a convincing balance of pathos and stubbornness. Clare Denton, as his wife, openly enjoys the malice inherent in the part, and works well with Oliver Baird’s Hunter in completing the emotionally volatile triangle.

The play stands as a prescient vision of a postwar Britain in which the primary criterion for success moves from ability to popularity; the recognition, as early as 1948, that Crocker-Harris and his ilk were becoming obsolete, is the key to its importance in theatre history. Beyond this, though, the play is also a beautifully handled examination of the tension between private despair and public dignity. It is interesting, to anyone familiar with the rather melodramatic climax of the film, to experience afresh Rattigan’s original, sparse ending which leaves the outcome of Crocker-Harris’s final act of defiance entirely unresolved. It is a brave move, and all the better for it.

In contrast, Harlequinade is a light-hearted and fast-paced farce satirising the world of the touring theatre company in the mid twentieth century. A tale of vanity and spinelessness, the play is set on the stage as a production of Romeo and Juliet, as two ageing stars rehearse the roles they have been playing for decades, and for which they are clearly no longer suitable.

Here, Rattigan seems uncertain as to the nature of the genre he is working in; what begins as a witty and verbally dextrous dismantling of Shakespeare’s doomed romantics soon descends into an increasingly implausible pantomime of mistaken identity, Brian Rix-esque misunderstandings and a very tenuous storyline involving bigamy, illegitimate children and amnesia, whose resolution seems beyond the author’s reach. That said, there is plenty of sharp dialogue along the way to entertain, and strong performances, particularly from Simon Vail as the fading Romeo, make the time pass amiably enough.

This unlikely paring, the serious work with the broad farce, is made all the more curious by the author’s deliberate decision to mount them as companion pieces. It is undoubtedly the former that has stood the test of time, but as an evening’s entertainment, these two short works represent good value from an impressive amateur company.